Restoring white seabass populations at Hubbs-Seaworld Research Institute

By Chris Uyeda

Today we headed to Agua Hedionda Lagoon in Carlsbad to visit the Hubbs-Seaworld Research Institute (HSWRI). Despite its name, HSWRI is not directly connected with Seaworld theme parks. The two institutions have different funding, administration and missions. There wasn’t a simple answer as to why they share the same name but I promise you there weren’t any dolphin shows today.

While there are multiple HSWRI sites, the Carlsbad location focuses on stock enhancement for the California white seabass. Stock enhancement is basically the process of growing and releasing fish into the wild, with the goal of increasing (ie. enhancement) the size of the wild populations (ie. stock).

Why would HSWRI want to increase the population of white seabass? The quick answer is that in the early 20th century seabass population were in trouble. Decades of both commercial and recreational pressures meant too many fish had been taken out of the ocean. Restoring fish populations is a major challenge – one that takes collective action from anglers, managers, and researchers to name a few. But to oversimplify, when fish populations decline there are two options – take out less or put more in. HSWRI’s role was to focus on the latter, and thus was born the hatchery.

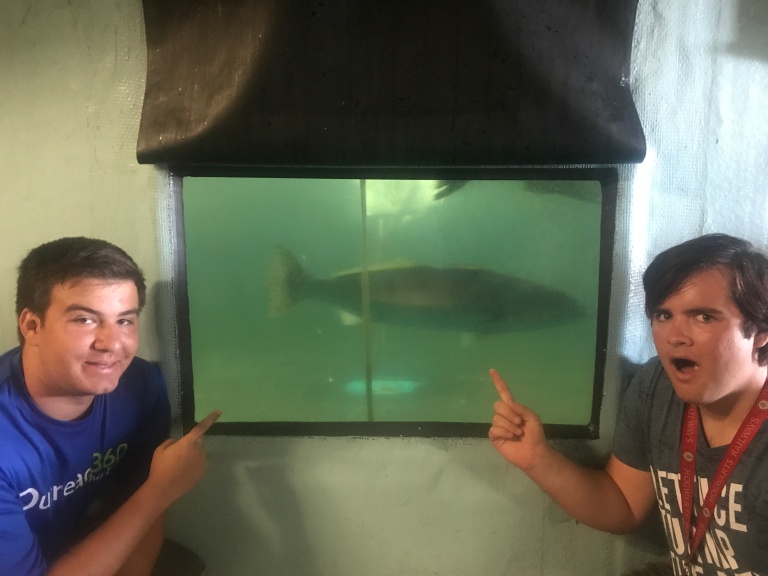

How exactly they do this (i.e. grow more fish) is what we came to find out. It starts with brood stock, large adults that are caught from the wild and kept in the hatchery in order to produce eggs.

Seabass typically spawn in the summer, when the water is warm and sunlight is plentiful. But by controlling these factors in the hatchery, researchers are able to get brood stock to produce eggs year round. And they produce a lot of eggs. One female will produce about 1.8 million eggs per spawn and they spawn every 2 weeks. Of course, very few of these eggs make it (either in hatchery conditions or the wild), a basic feature of their evolutionary reproductive history.

Once the eggs hatch, they are fed brine shrimp (aka sea monkeys) for about 20 days before transitioning to dry food. These tiny seabass stay at the hatchery until they are about 3 inches in length at which point they are transferred to a grow out facility.

These grow out sites are essentially large pens in bays, lagoons, and harbors where the fish can continue to increase in size prior to release. The transition helps acclimate fish to the ocean and increasing their size means they will be less vulnerable to predators, both of which increase their chances of survival. The grow out facilities are located throughout Southern California and seabass will stay there until they are about 14 inches long.

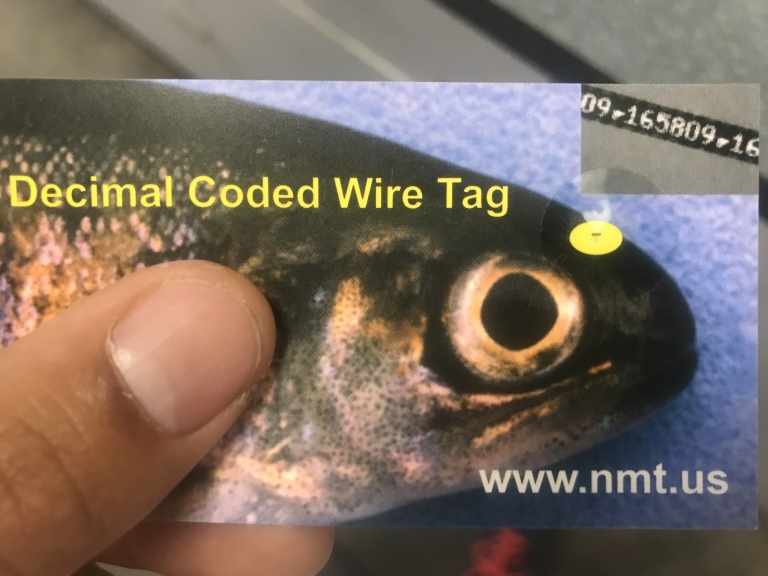

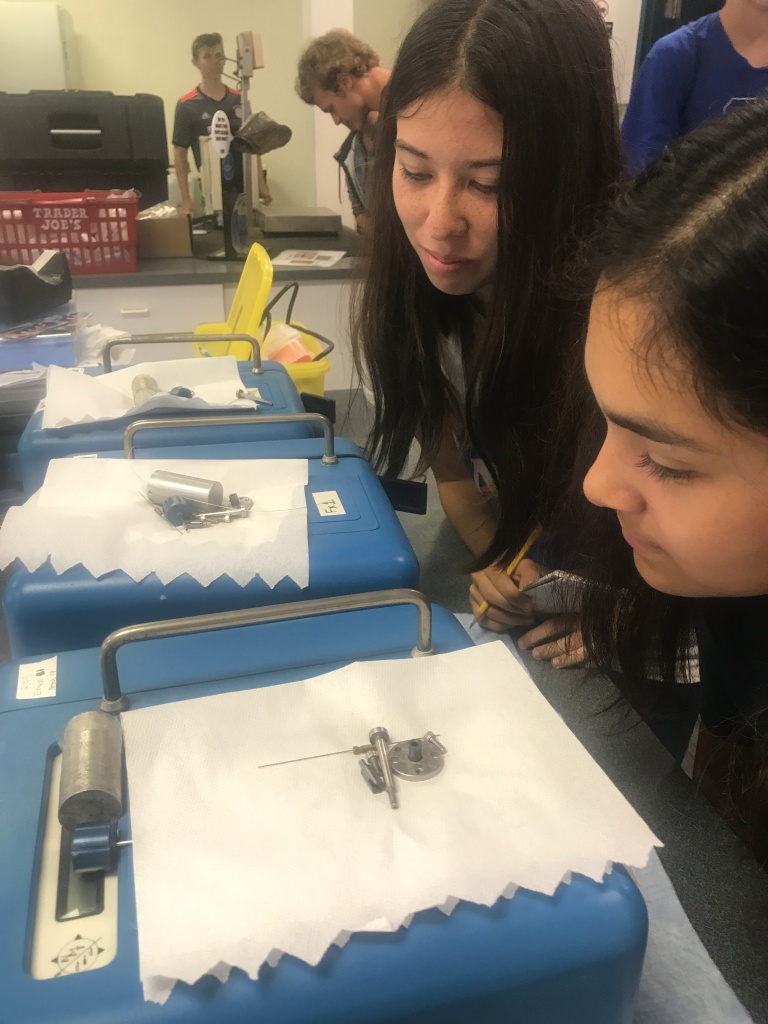

But before they are released, juveniles are tagged with an ID marker. The ID is a teeny, tiny piece of metal injected into the head of the fish.

When anglers catch seabass, they are encouraged to return the head so researchers can check to see if they came from the hatchery. Collecting data on where and how often hatchery raised fish are caught in the wild can help inform the impact of the hatchery.

So what has been the impact? It’s hard to say exactly. Determining population sizes is a challenge in of itself and even when good estimates are in place explaining why populations go up or down is the result of many factors. So isolating the role of the hatchery is challenging. But the hatchery releases about 350,000 juveniles annually and since the program started in the 1980’s, HSWRI has released over 2.4 million seabass.

When you walk through the facility, it’s an astonishing operation. Especially considering the whole thing runs with a team of about 10 people. And while funding is always a challenge, we learned that if you’ve ever bought a marine fishing license from the Department of Fish and Wildlife, you’ve helped fund this program.

We ended the day with standup overlooking the lagoon. And while I was listening to what students took away from the day I was struck by our location. Just across the lagoon is the Carlsbad Aquafarm , the site we visited on our very first day of class. It was a one of those “full circle moments”, that made me reflect, on our penultimate day, just how far we’ve come.